«A strange workshop were people pay 20,000 lire for every kilo less…»

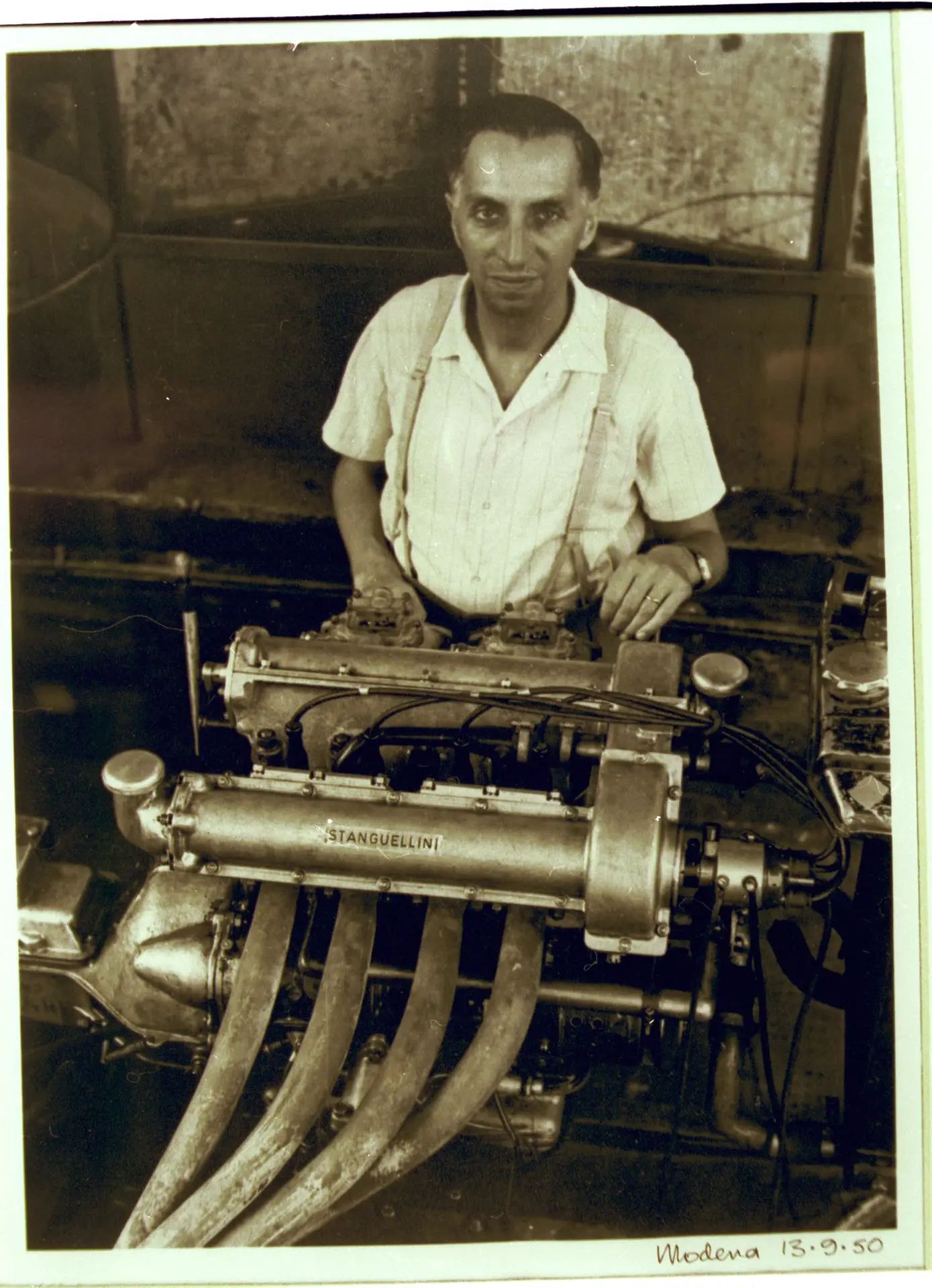

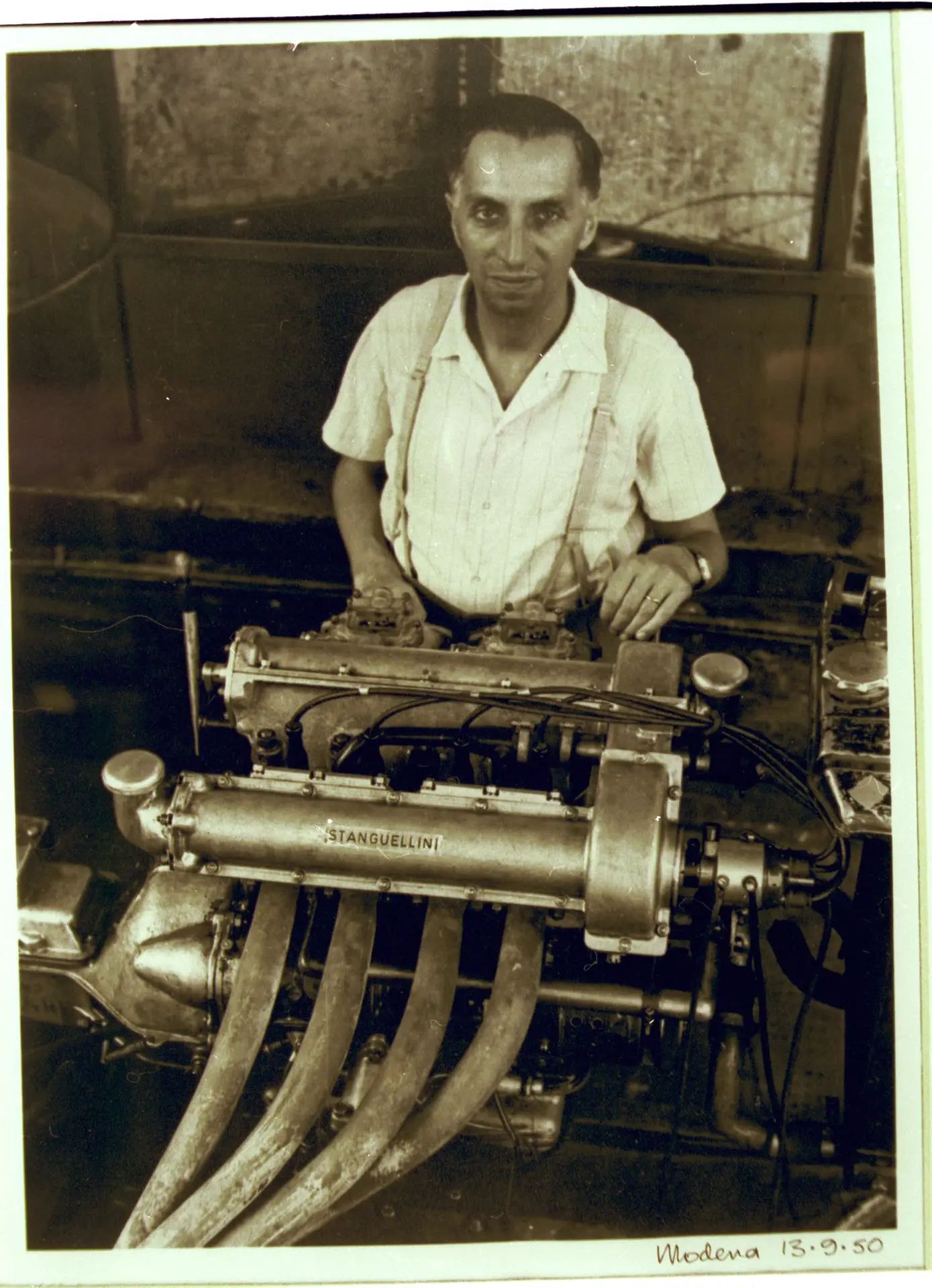

These were the musings of journalist Guido Piovene, who set off in 1953 to travel the length and breadth of Italy for three years, jotting down his observations as he went. During this adventure, when wandering around Modena, he stumbled across Vittorio Stanguellini’s workshop: a moment that would later be immortalised in his cult reportage Viaggio in Italia (1957). Before we embark on our own journey through this fascinating chapter in the history of the Motor Valley, let’s pause to take in a few more lines from Piovene’s reflections.

«Another curious thing is Stanguellini himself: “the transformer”. He transforms ordinary Fiats into racing cars or grand tourers […]. Underpinned by calculation and precision, Stanguellini’s craft is all about making cars lighter; with immense patience, he puts holes in everything he can to make them weigh less»

He continues by exclaiming that «small, ordinary engines can do 180 kilometres per hour». This «strange workshop» marks the starting point for our very own journey, not in space but in time: keeping our feet firmly in Modena, we travel back to another type of trade.

This particular workshop was managed by Celso Stanguellini from 1879. At just 20 years old, he set up the eponymous company, which did not sell cars but rather musical instruments – specifically, orchestral timpani. Celso’s success spiralled when the company patented a mechanical tuning device, so much so that the Timpani Sistema Stanguellini eventually became a staple tool in the legendary Arturo Toscanini’s orchestra.

It’s fascinating that Modena’s oldest racing car manufacturer has its roots in a percussion instrument, whose pitch is determined by the tension of its skin. Even more so when considering that this tension is adjusted through mechanisms, as fate would have it, activated by a pedal.

At the dawn of the century, Francesco Stanguellini With a deep passion for engines, he also dabbled behind the wheel as a driver himself.

Francesco also became Modena’s first Fiat representative, forging a long-lasting relationship between the Stanguellini name and the Turin brand. In 1908, he purchased the first MO1-plated Fiat Tipo 1. After that, his work straddled two distinct paths: car tuning on the one hand and motorbike racing on the other. Initially, it was in fact in the world of two-wheelers that Scuderia Stanguellini truly made its mark seventeen years later, taking the Modenese Mignon motorbikes to victory in 1925.

In 1932, Francesco’s untimely death at the young age of 53 meant that the responsibility of leading the company was suddenly thrust onto his then 20-year-old son, Vittorio.

Born amidst the roar of engines, Vittorio quickly recognized the potential of focusing the company’s efforts on car tuning. In 1936, Stanguellini began producing its own models, based on Fiat and Maserati chassis. The following year, the Stanguellini Team was born, formed of four drivers: Baravelli, Rangoni, Severi, and Zanella. This marked a turning point in the company’s journey, igniting its success in the racing world both in Italy and beyond.

Only the war halted Stanguellini’s journey, but even this was temporary, with the team resuming its streak of successes soon after. In 1946, the team triumphed in the Campionato nazionale assoluto Sport and the Belgian Grand Prix. Then came the golden year of 1947, when the cars constructed and tuned by the Modenese brand triumphed week after week, driving their supporters wild with excitement: an adventure made even more epic by the fierce duels with compatriot Scuderia Ferrari cars.

The years from 1947 to the early 1950s marked a period of radical technical innovation for Stanguellini. During this time, the company began using high-strength steel tubes for its chassis, achieving exceptional rigidity and reduced weight. It was also in this period when the two twin-cam engines — the 750 and the 1100 — were developed, becoming the backbone of the Modenese manufacturer’s venture in the years that followed: these twin-cams would in fact go on to secure five victories over nine years in the Campionato Italiano Classe 750 Sport Internazionale, and notably took home First Place at the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1957.

It is within the historical context of the 1950s that the encounter between Guido Piovene and Vittorio Stanguellini takes place, in the workshop of a man who had devoted his life to lightness. An anecdote shared by Vittorio’s niece, Francesca — who we will introduce later — beautifully captures the essence of this vocation. She tells Marco Panella about Vittorio and his bunch of keys, heavy from all the different sets for his home and workshop. It was only when he thought of drilling holes into them that they became lighter: just like his cars.

In the workshop along with Vittorio and Piovene was another small yet significant presence: Francesco Stanguellini, named after his grandfather, who would zip around on his little Formula Bambini, a toy his father had built for him that could reach speeds of up to 60 kilometres per hour. There’s a wonderful moment captured in Piovene’s interview with young Francesco, which we find in the radio version of Viaggio in Italia, broadcast by RAI between 1954 and 1956, where we hear his tiny voice accompanied by the music of his beloved toy: it’s clear that speed was in the Stanguellini family’s blood long before their cars.

«Little Francesco, are you going to compete with the likes of Fangio and Ascari?»

«I hope so…»

The Stanguellini story continues with year after year of Formula Junior victories: a pivotal chapter shaped by a fruitful partnership with the legendary Juan Manuel Fangio mentioned above. Through guidance and testing, the Argentinian driver played a key role in the Stanguellini Formula Junior 1100’s trophy-laden success that ran from the fifties through to the seventies.

This period also saw twenty-four world speed records: a triumphant streak that all started when Pietro Campanella and Angelo Poggio brought their Guzzi-engined Nibbio single-seater to the workshop for fine-tuning. Soon after this, the astonishing Colibrì was built, featuring a Stanguellini chassis and bodywork designed by Franco Scaglione. With its radical aerodynamics, this small car set an impressive six world records in 1963.

Finally, we cannot forgot the Junior Delfino and Vittorio Stanguellini’s very last sporting creation, the Formula 3. Unfortunately, the economic forces that Stanguellini has to contend with turned out to be a mountain too big to climb, and the team’s sporting success suffered as a result.

Vittorio Stanguellini passed away in December 1981 at the age of 71. Without him, the team that had driven a century of racing began to fade. However, the passion of his son Francesco, now grown up, and the power of the Stanguellini legacy lived on. The company continued, focusing on the restoration and tuning of historic cars, alongside the creation of the eponymous museum.

As the history of the Stanguellinis teaches us, there is always someone, whether a boy or a girl, cradled by the echo of car engines, ready to carry the torch. In this case, it was Francesca Stanguellini who took over from her father Francesco and now manages the Museum, where these speed icons now rest immobile — fortunately for us, though perhaps not so much for them. A magical place, in the sense that visitors deal with a history of transformations: from music to engines, from engines to more powerful engines, from chassis to lighter chassis, from all this to legend.

Partner involved:

Area involved: