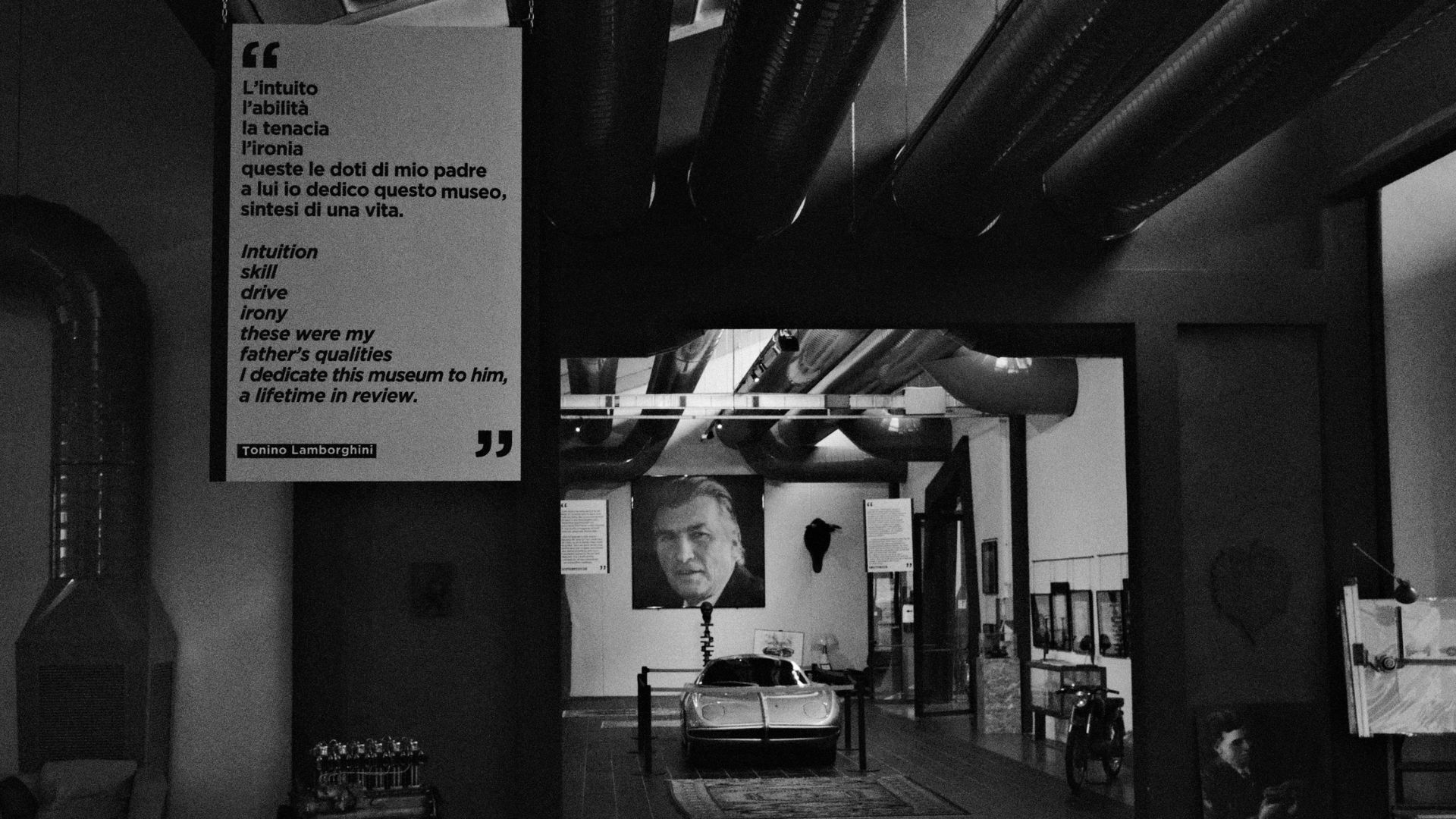

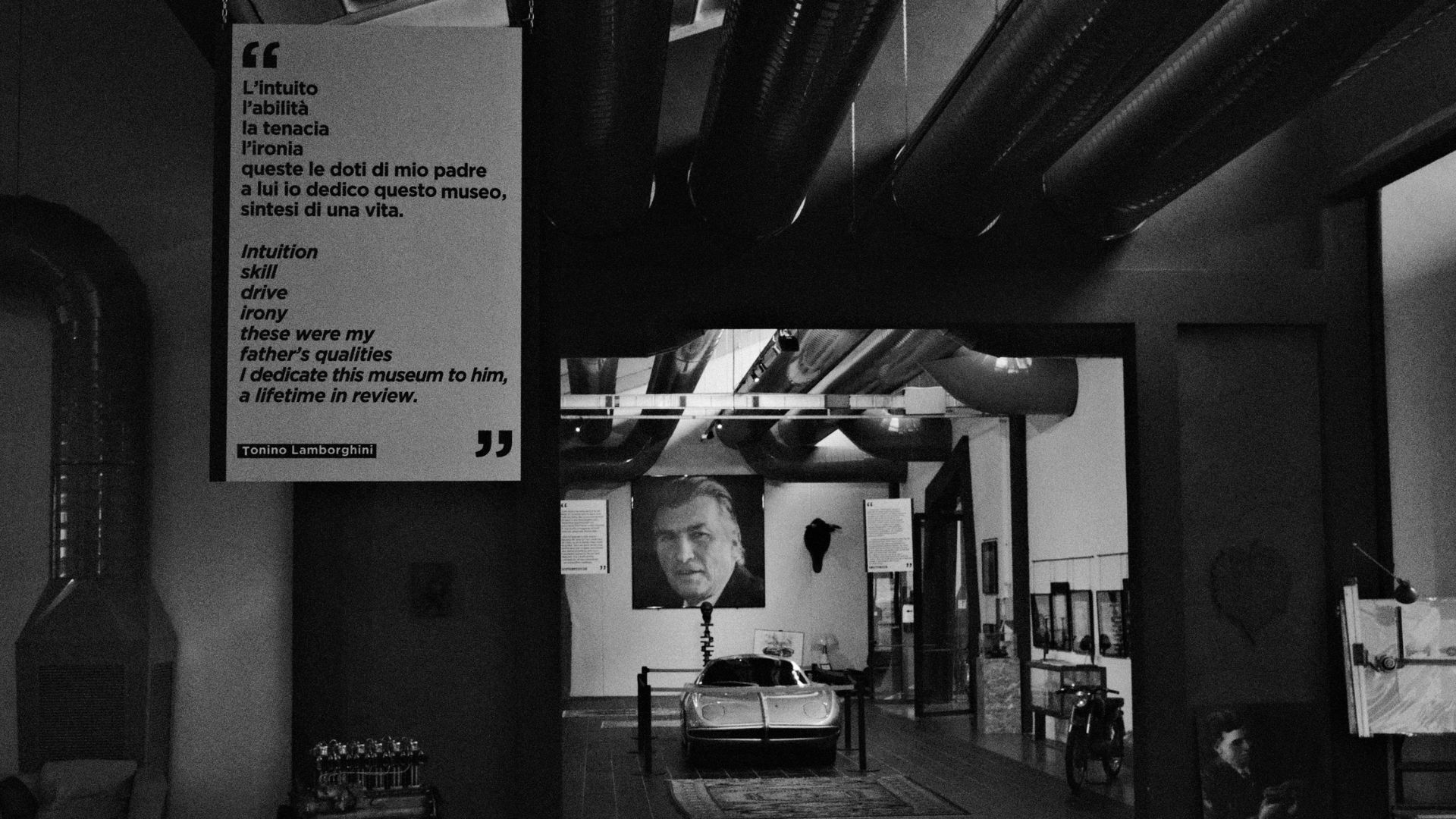

We went to the Ferruccio Lamborghini Museum in Funo di Argelato to hear a son talk about his father, and to delve deeper into what drove him to dedicate a space we thought we already knew quite well. Today, on the anniversary of Ferruccio’s birth, we can say that this experience has taken on a new meaning for us. We’ll do our best to share it with you: our conversation with Tonino Lamborghini began on the couch of a room near the entrance…

As soon as my father died, I built a museum that was much more beautiful than this one — much more beautiful — but it was in Dosso, a small town just a stone’s throw from Cento. It was designed by architect Oreste Diversi from Imola, who brilliantly interpreted an idea I had. Within a few days he showed me a sketch, and it was exactly what I wanted. Basically, a structure shaped like a spaceship, or perhaps a giant swallow, that with the play of night lights and the local fog seemed to lift off the ground. Why a spaceship? Because it goes up to the sky, presumably toward the creator of the things contained within it. It stood for over twenty years, but over time fewer and fewer people visited — those who wanted to see it had already seen it… Then this facility became available, and I completely revamped it.

What kind of emotions does this museum make me feel? Well, I honor my father, I honor my mother: the company was born from these two young people who got married. He was a mechanic, she handled administration. And from that, a legend was born.

I started searching for old Lamborghini tractors when I was just a kid, fourteen or fifteen years old. I’d look for them in the farmyards. Sometimes a worker would give me a tip: «Hey, I think I saw one over there…». So I’d go under a fake name on my Vespa. I didn’t even have a driver’s license yet. I used a fake name because if I’d said I was a Lamborghini, they would’ve sold them to me at triple the price. A curious and wonderful thing is that I found them in chronological order: the first model, then the second, and so on. How do you find old, discarded farm machinery that doesn’t even start, in order? To me, it was a sign of destiny. Someone up there really does love us.

My father wasn’t too happy that I spent my time hunting down and restoring those things instead of studying. I did it secretly anyway. Not only that: since I was a child, I started saving parts from his office, always in secret. My father never knew that I had the original office from their first little workshop. How does a ten-year-old kid manage to hide and preserve an entire office? I couldn’t possibly have had a museum in mind back then — I just did it. I still wonder how it was even possible.

Only my mother knew something — not everything… just a little. «Old junk dies in the house of fools» my father used to say, quoting an Emilian proverb. That’s why there wasn’t a single antique piece of furniture in our house. Anything older than five or six years was given away. To him, life was about moving forward and leaving the past behind.

Much later, he started to change his mind a little. When I began showing him my collection of tractors and a few cars — not as many as I have now, because I couldn’t afford them — he wasn’t unmoved. I started up the first Carioca tractor: vroom, vroom, vroom… and his eyes got misty. I thought he’d be mad, but instead he put his hand on my shoulder and said: «Bravo, bravo. I was your age and had a lot of debt. Keep going, keep going…». «One day you’ll make a museum — and remember: build it near a highway.» He said that too. From that moment, he sometimes helped me financially with my project, helping me buy the more expensive pieces.

«I started up the first Carioca tractor: vroom, vroom, vroom… and his eyes got misty.»

What was my father like? The only thing I’ll say is that fathers used to be different. There wasn’t the same closeness — fathers didn’t play with their kids. Maybe the love was the same, but the attitude was different. But that was true for everyone, from top to bottom. As for whether I realized what he was creating at the time… kind of. I realized that producing cars brought worldwide — not just national — recognition. I understood that he had built the most modern car of the time — not just in terms of design — and that a few months after its launch, it had been purchased by the MoMA in New York (the Miura). But when you grow up surrounded by it, everything feels normal. Like it was normal for my father to let me drive the Miura to take my friends for a ride. A brilliant insight of his: it’s people who don’t know how to drive who can really tell if a car is good — if it’s hard or easy to handle. Of course a professional driver knows how to use the clutch and gearbox… I also knew I was “the Lamborghini kid” in town — the one whose father made tractors — while other kids rode bikes to school and I got driven, though partly just because of the distance. But I lived it like it was normal.

When I’m alone at the Museum, sometimes I sit in his office to focus. Another thing I like to do… Tonino pauses, thinking… oh yes! There’s an old Alfa Romeo I really love. It’s the one that used to take me to school. Every now and then, I get in that car and sit there for a while, remembering my childhood.

Let’s go.

We get up from the sofa and walk toward the area dedicated to Lamborghini Tractors.

Where do we start? Let’s start with that orange tractor, the first one — the 1948 Carioca. The one I started up in front of my father, and thanks to which I gained his support.

Tonino briefly shows us a Jeep, explaining how the first tractors had military origins. He also points out some mechanical features of the machine. Soon we begin to realize just how deep his technical — as well as historical — knowledge of the displayed pieces really is. In front of the Carioca, he particularly focuses on the operation of the invention that made it famous: the petroleum vaporizer. Not diesel, he stresses. Petroleum was cheap, readily available, and that made the tractor extremely competitive on the market.

He also shares an anecdote that excites him particularly. It begins in 1949, when the Fanfani Law came into effect. To encourage domestic production, the law provided financial and tax incentives to any farmer or company — especially farmers — able to produce an entirely Italian-made tractor…

You had to rush to make a fully Italian product: but how to do that in just a few months? It was a tough race. So my father, who at the time was a nobody, went to Germany to a company that made engines — MWM — and asked if he could get their engine under license. They looked at him and laughed. And he replied: «Well, if you give me the license, fine. Otherwise, I’ll copy it.»

He was apparently persuasive enough to get the license. He came back and started installing those engines on his tractors (everything else was Italian-made). A year later, that engine was so thoroughly modified that my father went back to MWM in Germany and said: «Here, this is my engine — test it. If you like it, you pay me.» And that’s how it happened: the last of the Italians sold his product to Germany. A story that still gives me goosebumps.

We walk past a few small cars Ferruccio had built for himself, including the one he drove in the Mille Miglia. Tonino has driven them too, and calls them «rockets.» Then he lingers on a detail in the Museum that not all visitors notice…

Like it was normal for my father to let me drive the Miura to take my friends for a ride. A brilliant insight of his: it’s people who don’t know how to drive who can really tell if a car is good — if it’s hard or easy to handle.

Why do you see the typewriter, the mimeograph, the moped, the motorcycle, the record player, the vacuum cleaner, the first portable television, and so on? Because I like to show what was going on in the world around the Lamborghini products — to draw parallels with their contemporaries. What was the motorcycle of the time, how did people write…

Another piece catches his attention, and suddenly we’re deep into new stories, with Tonino working to help us understand how technologically advanced Lamborghini products really were. Like a child fascinated by everything around him — if not for his expert command of every detail — you’d think it was his first time in the Museum. A tractor, a helicopter, a Fiat Topolino, and we move to another room. Here we also see Lamborghini’s production of boilers, burners, and air conditioners from the ’60s, which, Tonino tells us, polluted far less than others of the time. And much more: a Porsche, a Vespa, a rare Fiat 1004, the Giulietta — “Italy’s sweetheart.”

I want to show you something special…

We step into a more secluded room and find ourselves in front of an old, rusty tractor, worn down by time.

Come see time itself… This is time: it’s that same orange tractor we saw earlier, after 75 years of corrosion. I think it’s a work of art. Because if you tried to make it look like that on purpose, you couldn’t.

We also walk past the famous Ferrari clutch that led to Ferruccio Lamborghini’s dispute with Enzo Ferrari.

If that argument had never happened, Automobili Lamborghini might never have been born.

We then enter the room dedicated to the brand’s most iconic cars, where Tonino can finally catch his breath.

Here, I have nothing to say. You all know more than I do.

In the silence, we understand the meaning behind his words. But we’re not so sure.

Among these icons of automotive history is also the Fast 45 Diablo Class 1 offshore boat, measuring 13.5 meters, powered by a Lamborghini engine and eleven-time world champion: a Bull that turned water into its asphalt. It’s red, but not the same red as Ferruccio Lamborghini’s personal Miura SV. A one-of-a-kind shade that frames his eyes and lashes. Hard to look away when it’s nearby. For all the ink spilled about this goddess, Tonino still owes us a few words.

People ask: «But why was it so successful?» Well, come on! Where there’s technology, you make history. People admire the beautiful lines, but you’ve got to look under the surface. Beautiful outside and beautiful inside.

So we talk about the team that shaped it: engineers Dallara and Stanzani, coachbuilder Bertone, designer Gandini… Ferruccio Lamborghini understood land, he understood mechanics, and he understood people. He always picked brilliant collaborators, and we wondered if ‘intuition’ might be the one word that characterizes him.

He rarely made a mistake with a manager, engineer, or worker. Very rarely. He had an incredible instinct. Even if a kid walked by, he’d say: «Hey! Still in school? Come work for me when you’re done.» And he was always right.

That leads Tonino to share his thoughts on the origins of Italy’s Motor Valley.

Why was the Motor Valley born here? Because of the Aldini-Valeriani schools, founded in the late 19th century. And because in Cento, where Lamborghini was born, where VM was born… there was the Taddia brothers’ school. They were vocational schools. Almost none of our technicians were engineers — only two were – the rest were mechanical experts. People who knew how to get their hands dirty, while engineers were more theoretical. Why did they all start here? Maserati brothers, Ducati, Bugatti, and many others? Thanks to those schools. Now I don’t know if Bugatti ever went to Aldini Valeriani… Still: credit where credit is due, to these two schools.

In Bologna, where my father went to school on that moped you see there — he points to it — riding “back and forth,” there was a company called Officine Righi, located along the ring roads. They had the exclusive rights to service military vehicles. If you worked there, you were exposed to all the latest mechanical technology. My father worked there for free — he’d be the first to arrive and the last to leave. He learned so much. At fifteen or sixteen years old. From Renazzo. On that very moped. That’s something…

More than an hour flew by listening to Tonino. Then he said goodbye like a man from another time, and almost without realizing it, he was gone. There’s a famous quote by Goethe that says: «What you inherit from your father must first be earned before it’s yours.» In defiance of any passively acquired inheritance, Tonino began to reclaim his father’s legacy well before bureaucracy would advise it, with the stubbornness to go against even his father’s wishes. Perhaps managing to find a way out — or at least a good compromise — between that Emilian saying Ferruccio used to repeat, urging him to get rid of old stuff, and the forward-looking spirit that lies at the heart of the Lamborghini name. Because the Ferruccio Lamborghini Museum is more a place of inspiration than of nostalgia.

Partner involved:

Area involved: